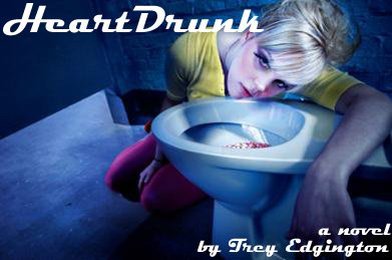

I'm currently shopping my sorta-fictional memoir HeartDrunk to literary agents, in hopes of becoming rich and quitting my day job.

HEARTDRUNK follows Taylor Nimitz though his twenties as he falls in and out of love with everyone he meets, from classmates to bartenders to strippers. He is a writer who seeks and finds an increasing amount of chaos. With each passing love, he copes with the excitement and loss with alcohol, finally losing control and beginning his journey in “recovery.” The story ends shortly after Taylor gets out of the hospital, having almost died from acute pancreatitis. His friends and family tell him how lucky he is, but as always, he’s not so sure.

Readers of Charles Bukowski, Tucker Max, and Augusten Burroughs will find HEARTDRUNK appealing for its brutal honesty, humor, and sex set in a contemporary American city. Though a large part of the novel is about recovery—appealing to readers of that growing genre—Taylor’s experiences as an educated, middle-class man who finds himself in state-sponsored treatment facilities add a twist and comment on the current state of social mental health care services available. The confessional and conversational nature of the narrative voice gives the reader that the narrator is telling them a story while sitting together at a bar.

Here is a short sample from the book:

It was my first day in the worst rehab in the world. An ex-con treatment center, though I'd never been to jail. During my first meeting--one of thirteen that day--I noticed an old black guy sitting a couple seats down from me. He was wearing a green jacket from the Masters’. Obviously a replica, though a good one. He was also wearing a clean, white t-shirt, khakis, and some Adidas shell-toes with red stripes. The thing about this guy was that he always had tears in his eyes. It didn’t shock me to see someone about to cry in there; I knew I would want to cry before long. And though I never saw him without tears in his eyes, I never saw him cry. There was a blocked intelligence in his eyes, like he was still sad about being trapped in himself and aware of it. He wore the same clothes every day, though they always looked fresh and clean. I never knew his name. No one I became friends with knew it. He smoked cigarettes rolled in brown paper.

We had meetings the rest of the day. Each of them lasted fifty minutes with a ten minute smoke break afterwards. It turned out that there were never counselors in the meetings—that day at least. Thankfully, there weren’t any more “speaker” meetings. They would start with a “burning desire” for a topic. The leader for that meeting would ask if there was a “hot topic,” and someone would say they had one. It usually started out with something to do with addiction. Out of sixty guys, maybe ten spoke the whole day. I never spoke, except when I had to introduce myself at my second meeting. I told them I was an alcoholic, Cherokee/Irish, college English teacher. From then on, I was known as “Professa.” The meetings were usually boring and repetitive. Every once in a while, someone would tell what I later learned was called a “war story.”

“Terry, Family.” That's how you had to introduce yourself to speak. Your name, Family.

“Terry,” everyone said.

“This one time I was at the motel with a couple big booty freaks and my cousin. Y’all know what I mean?”

“Hell yeah,” all the black guys said.

“I just got my disability check, so I was rollin. My cousin wasn’t really into drugs, but he loved them ho’s. Anyway, me and Funquita was sitting there and befoe I knew it, she stuck that pipe up to her pussy.”

I knew I was about to hear some crazy shit.

“Yeah, so Funquita take a big ol hit off that pipe with her pussy. And you ain’t gonna believe this shit. She started blowin out…Professa, what you Indians call it when you use smoke to talk to people and shit?”

I wasn’t expecting anyone to talk to me, so it took me a second to respond. “Umm…Smoke signals? I'd seen that in movies like everything else. It's not like I grew up on the rez. Just another white boy claiming to be somehow marginalized.

“Yeah, smoke signals. Thanks Professa. That ho was blowing smoke signals out her pussy with that crack smoke.” Terry made this motion over his crotch with his hand like it was a wet blanket breaking up the smoke. Everyone was laughing. I almost pissed myself. I figured it was bullshit, but it was a hell of a story so far.

“You know what them smoke signals was sayin? ‘Come fuck me, nigga. Come fuck me.’ I couldn’t believe that shit, but you don’t have to ask a nigga like me twice if I wants to fuck. I was all up in the crack-smoke-signal-blowin pussy in the blink of an eye. And mmm, let me tell you; it was good.”

He went on with his story. After a while, I started to wonder what the hell it had to do with addiction. I was still wondering what the hell I was doing there. I’d never smoked crack. I wasn’t black. I’d never been to that kind of motel. I was just hanging out at a place with shitty food and funny but pointless stories. How in the fuck is this supposed to keep me sober? I really was trying to figure it out. I figured I should learn something if I had to stay in this shithole. There had to be something to it. Finally, Terry got to the point.

“But you know what happened the next mornin? No, I know y’all know what happened.”

Almost everyone said, “Hell no. She didn’t?” I had no idea what happened.

“Oh, hell yeah, she did. When I woke up, they wasn’t no rock. Them hos was gone in the wind, and they wasn’t a dime in my pocket. I spent up my whole check in one night, and no matter how many times I tell myself I ain’t gonna do that again, I do it anyway. I know I ain’t gonna have no money fo the rest of the month, but I get them hos and rock no how. I always think it’s gonna be different this time.” He looked around at us—all the humor gone from his voice. “It ain’t never gonna be different.”

Then Terry said, “I know that shit’s gonna happen now, but I don’t know how to stop it. I’m not sure if I’d know what to do with a real woman if I hadn’t smoked a little bit first. You know? It ain’t even bout the drugs anymore.”

One dumbass, Uncle Remus-looking bastard said, “Just trust in Jesus.” Everyone, from the Christians to one Satan Worshipper, looked at him like he was retarded. We went on our smoke break and broke into our groups. I didn’t have a group yet, so I just paced. Everyone was talking about sports.

HEARTDRUNK follows Taylor Nimitz though his twenties as he falls in and out of love with everyone he meets, from classmates to bartenders to strippers. He is a writer who seeks and finds an increasing amount of chaos. With each passing love, he copes with the excitement and loss with alcohol, finally losing control and beginning his journey in “recovery.” The story ends shortly after Taylor gets out of the hospital, having almost died from acute pancreatitis. His friends and family tell him how lucky he is, but as always, he’s not so sure.

Readers of Charles Bukowski, Tucker Max, and Augusten Burroughs will find HEARTDRUNK appealing for its brutal honesty, humor, and sex set in a contemporary American city. Though a large part of the novel is about recovery—appealing to readers of that growing genre—Taylor’s experiences as an educated, middle-class man who finds himself in state-sponsored treatment facilities add a twist and comment on the current state of social mental health care services available. The confessional and conversational nature of the narrative voice gives the reader that the narrator is telling them a story while sitting together at a bar.

Here is a short sample from the book:

It was my first day in the worst rehab in the world. An ex-con treatment center, though I'd never been to jail. During my first meeting--one of thirteen that day--I noticed an old black guy sitting a couple seats down from me. He was wearing a green jacket from the Masters’. Obviously a replica, though a good one. He was also wearing a clean, white t-shirt, khakis, and some Adidas shell-toes with red stripes. The thing about this guy was that he always had tears in his eyes. It didn’t shock me to see someone about to cry in there; I knew I would want to cry before long. And though I never saw him without tears in his eyes, I never saw him cry. There was a blocked intelligence in his eyes, like he was still sad about being trapped in himself and aware of it. He wore the same clothes every day, though they always looked fresh and clean. I never knew his name. No one I became friends with knew it. He smoked cigarettes rolled in brown paper.

We had meetings the rest of the day. Each of them lasted fifty minutes with a ten minute smoke break afterwards. It turned out that there were never counselors in the meetings—that day at least. Thankfully, there weren’t any more “speaker” meetings. They would start with a “burning desire” for a topic. The leader for that meeting would ask if there was a “hot topic,” and someone would say they had one. It usually started out with something to do with addiction. Out of sixty guys, maybe ten spoke the whole day. I never spoke, except when I had to introduce myself at my second meeting. I told them I was an alcoholic, Cherokee/Irish, college English teacher. From then on, I was known as “Professa.” The meetings were usually boring and repetitive. Every once in a while, someone would tell what I later learned was called a “war story.”

“Terry, Family.” That's how you had to introduce yourself to speak. Your name, Family.

“Terry,” everyone said.

“This one time I was at the motel with a couple big booty freaks and my cousin. Y’all know what I mean?”

“Hell yeah,” all the black guys said.

“I just got my disability check, so I was rollin. My cousin wasn’t really into drugs, but he loved them ho’s. Anyway, me and Funquita was sitting there and befoe I knew it, she stuck that pipe up to her pussy.”

I knew I was about to hear some crazy shit.

“Yeah, so Funquita take a big ol hit off that pipe with her pussy. And you ain’t gonna believe this shit. She started blowin out…Professa, what you Indians call it when you use smoke to talk to people and shit?”

I wasn’t expecting anyone to talk to me, so it took me a second to respond. “Umm…Smoke signals? I'd seen that in movies like everything else. It's not like I grew up on the rez. Just another white boy claiming to be somehow marginalized.

“Yeah, smoke signals. Thanks Professa. That ho was blowing smoke signals out her pussy with that crack smoke.” Terry made this motion over his crotch with his hand like it was a wet blanket breaking up the smoke. Everyone was laughing. I almost pissed myself. I figured it was bullshit, but it was a hell of a story so far.

“You know what them smoke signals was sayin? ‘Come fuck me, nigga. Come fuck me.’ I couldn’t believe that shit, but you don’t have to ask a nigga like me twice if I wants to fuck. I was all up in the crack-smoke-signal-blowin pussy in the blink of an eye. And mmm, let me tell you; it was good.”

He went on with his story. After a while, I started to wonder what the hell it had to do with addiction. I was still wondering what the hell I was doing there. I’d never smoked crack. I wasn’t black. I’d never been to that kind of motel. I was just hanging out at a place with shitty food and funny but pointless stories. How in the fuck is this supposed to keep me sober? I really was trying to figure it out. I figured I should learn something if I had to stay in this shithole. There had to be something to it. Finally, Terry got to the point.

“But you know what happened the next mornin? No, I know y’all know what happened.”

Almost everyone said, “Hell no. She didn’t?” I had no idea what happened.

“Oh, hell yeah, she did. When I woke up, they wasn’t no rock. Them hos was gone in the wind, and they wasn’t a dime in my pocket. I spent up my whole check in one night, and no matter how many times I tell myself I ain’t gonna do that again, I do it anyway. I know I ain’t gonna have no money fo the rest of the month, but I get them hos and rock no how. I always think it’s gonna be different this time.” He looked around at us—all the humor gone from his voice. “It ain’t never gonna be different.”

Then Terry said, “I know that shit’s gonna happen now, but I don’t know how to stop it. I’m not sure if I’d know what to do with a real woman if I hadn’t smoked a little bit first. You know? It ain’t even bout the drugs anymore.”

One dumbass, Uncle Remus-looking bastard said, “Just trust in Jesus.” Everyone, from the Christians to one Satan Worshipper, looked at him like he was retarded. We went on our smoke break and broke into our groups. I didn’t have a group yet, so I just paced. Everyone was talking about sports.